| Tweet

|

|

The

Star Larvae Hypothesis

Nature's Plan for Humankind

Part 2. Star Larvae

Silicates and Biogenesis

Biological life is cosmic, not terrestrial, in origin and scope.

The origin of life remains a puzzle, and theologians, scientists, and school board officials likely will continue mulling it over.

Whatever the outcome of such deliberations, this much is certain: If the universe spent its first moments as a ball of intense radiation, then life must have arrived sometime after the beginning. The first biological cells arose at some time and at some place once this universe got rolling.

According to the Big Bang cosmology, the primordial radiation cooled as it expanded, and from it condensed the first subatomic particles. These particles organized themselves into diffuse clouds here and there in the expanding universe. As each cloud grew more massive, it became denser owing to its own intensifying gravity. Eventually, pressure in the centers of these clouds ignited nuclear reactions, and the first generation of stars was born. These stars manufactured, as each generation continues to do, the species of atoms that are needed to construct planets, moons, comets, and the other components of solar systems.

Certain of nature's atomic widgets at some point got themselves assembled into simple molecules, organic macromolecules, and ultimately into the first viruses and bacteria. Where and how did this precise chemical engineering occur? (And is the process ongoing?)

'The formation of simple amino acids (e.g., glycine) is expected to take place in dense molecular clouds which may well be the cradle of life.'

Even such a tentative proposition was regarded as outrageous heresy in 1976, although now in 2004 it is regarded as obvious."

— Chandra

Wickramasinghe

A

Journey With Fred Hoyle

The prevailing assumption among research scientists has been that atoms and simple molecules first got arranged into macromolecules and cells somewhere on the surface, or near the deep-sea vents, of the early Earth. Numerous researchers have attempted to recreate the chemical, thermal, and other conditions that characterized the Earth once it cooled, in hopes of throwing light onto the chemical path that led to the first living cell. These laboratory efforts have left behind a legacy of inconclusive results, in which mixtures of simple molecules, such as methane, ammonia, carbon dioxide, and water, reacting chemically under the influence of electric sparks or other energy sources, have produced various consistencies of organic sludge.

That no life results from such experiments is to be expected. Using genomic analysis to determine rates of genetic change during evolution, researchers Alexei A. Sharov and Richard Gordon retrodict the time at which the first living cells arose and conclude that that date far precedes the origin of the Earth. That is, Earth isn't old enough to have hosted the origin of biological life. There simply has not been enough time for it to have happened since the Earth cooled to where it in theory could have happened.

Maybe a look beyond Earth is in order. Such a look reveals that material flows readily throughout the Milky Way—pushed by stellar winds, carried by comets and the newly discovered "nomad" planets that wander the galaxy unattached to any star, and by the circulatory effects of the galaxy’s own rotation. This means that geocentric assumptions can be set aside, and investigators can cast their nets almost anywhere in search of conditions conducive to the manufacturing of biological cells. There is no shortage of extremophile micro-organisms that thrive in conditions once thought inhospitable to life, potentially including extraplanetary environments. Examples include algae that survive more than a year exposed to the elements of outer space. (Even the species of stars include extremophiles.)

Silicon and Carbon: Made for Each Other

In industry, the manufacturing of molecular-scale devices is called nanotechnology. The search for the origins of biological life perhaps ought to focus on conditions that would favor a natural nanotechnology—that is, conditions conducive to manufacturing amino and nucleic acids and assembling them, and accompanying molecules, into viruses and bacteria. In other words, the focus should be on infrastructure equipped to support cell factories.

It turns out that the physical and chemical conditions inside stellar nebulae—the clouds of gas and dust from which solar systems condense—might be more conducive to hosting cell factories than would conditions on the surface of a freshly minted planet. The energetically dynamic environment inside an embryonic solar system seems to be ideally suited to the conjuring of biological life. And the element silicon seems ideally suited to play the role of sorcerer's apprentice.

—

R.

G. Collingwood

The

Idea of Nature

Silicon, like carbon, has a habit of bonding chemically with its own kind. This habit produces parallel macroscopic forms of the two elements. Both form three-dimensional crystals: carbon as diamond and the so-called buckeyballs or fullerenes and silicon as varieties of mineral crystals, or silicates, including precious stones and clays, not to mention electronic semiconductors. Packed less tightly, the atoms compose flexible chains, such as those that form the "backbones" of plastic polymers (carbon) and of synthetic rubbers, or silicones (silicon). These shared habits might predispose the chemical cousins to cooperate, given a suitable environment.

Such an environment, if it is to serve as a cell factory, would need an energy source and a way to direct energies precisely. It would need to shepherd chemical reactions up against the thermodynamic gradient through levels of increasing chemical complexity, away from equilibrium/entropy. It would need to catalyze organic reactions to build macromolecules as well as provide a physical structure to hold those molecules in place during their assembly into cellular substructures.

Given these criteria, silicon tops the list of potential midwives to assist during the birthing of biology. Silicon naturally bonds with various metals to form a variety of periodic and aperiodic crystalline forms. Silicate crystals potentially could serve as templates during organic synthesis. Nucleic acids and proteins could interlock handily with silicate crystals in secure arrangements during assembly into larger structures. This is the general line of thought developed in detail by A. G. Cairns-Smith in Genetic Takeover. (Proteins have crystal forms, and crystallography remains a primary laboratory technique for determining the structures of proteins, which also was the methodology used to determine the double helix structure of DNA.) Researcher Robert Hazen also has explored the chemistry of minerals as a factor in life's origin. These scientists locate on the ancient Earth the chemistry that produced the first living cells. But evidence continues to accumulate that suggests a complex organic chemistry active in outer space. See, for example, "Formation and Atmosphere of Complex Organic Molecules of the HH 212 Protostellar Disk" in The Astrophysical Journal, Volume 843, Number 1 and "Ribose and related sugars from ultraviolet irradiation of interstellar ice analogs" in Science, Vol 352, Issue 6282, 08 April 2016. In addition to sugars, at least one amino acid has been detected in space.

Because some silicate minerals have photoelectric properties—they can convert sunlight into electricity—silicates could serve as an energy source to drive organic synthesis. Some silicon crystals also possess piezoelectric properties. Under pressure, they generate an electric current. Phonograph needles exploit this property. Piezoelectric effects provide another potential source of energy to drive organic synthesis.

Biogenesis Via Silicate-Based Nanotech

Certain reactions that build complex organic molecules from simpler ones occur more readily in the presence of certain silicate minerals, which act as catalysts. Clay-catalyzed RNA synthesis, for example, has been demonstrated in the research of James Ferris at New York’s Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. NASA researchers Hugh Hill and Joseph Nuth have demonstrated the ability of amorphous iron and magnesium silicates to catalyze a variety of organic molecules from a gas mixture containing only carbon monoxide, nitrogen and hydrogen. Tim Tyler has posted a bibliography of references to silicate-mediated organic synthesis at http://originoflife.net/links/index.html).As to where silicate-managed cell factories might operate in nature, it turns out that all of the necessary ingredients are at hand in nearby space in what astronomers call "the local interstellar cloud." Our solar system is embedded in this cloud. The most abundant element in the cloud, as throughout the universe, is hydrogen, the starting material from which stars manufacture the other elements. Next in abundance in the local cloud are the elements carbon, oxygen, and nitrogen—the building blocks of organic chemistry—and silicon, magnesium, and iron, materials from which nature could construct catalytic assembly lines for the mass production of biological cells in space.

—

Aleister

Crowley

Truth, in Little

Essays Toward Truth

More specifically, researchers know that observations of young stars of intermediate size, so-called Herbig Ae stars, which resemble the sun in its infancy, and observations of the known contents of comets, suggest that, when solar systems form inside cooling stellar nebulae, silicate grains catalyze simple organic reactions to produce a variety of prebiotic organic molecules.

The prevailing model of interstellar grains, based on spectrographic analysis, is of carbonate shells covering silicate nuclei, and see here. The commingling of silicates and organics relies on reactions that require the heat and pressures found near a protostar. The grains, once coated with simple organics, then are transported by a "circulatory system" of material flowing from the center of the nebula out to the distance at which comets are thought to form. (The research by Nuth, Hill, and colleagues appears in Lunar and Planetary Science XXXIIII [2002], and see the paper "Protostars are Nature's Chemical Factories," by Nuth and Johnson in Lunar and Planetary Science XXXVI [2005]. A summary of this research is provided in "Constraints on Nebular Dynamics and Chemistry Based on Observations of Annealed Magnesium Silicate Grains in Comets and in Disks Surrounding Herbig Ae/Be Stars", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Vol. 98, No. 5, Feb. 27, 2001, 2182-2187.)

In a 2008 paper, Nuth and coauthors describe a self-perpetuating catalyst that could produce large quantities of organic material in protostellar nebulae. Here is the abstract from that paper, titled, A Self-Perpetuating Catalyst for the Production of Complex Organic Molecules in Protostellar Nebulae (The Astrophysical Journal, 673: L225-L228, February 1, 2008):

"When hydrogen, nitrogen, and CO are exposed to amorphous iron silicate surfaces at temperatures between 500 and 900 K a carbonaceous coating forms via Fischer-Tropsch-type reaction. Under normal circumstances such a coating would impede or stop further reaction. However, we find that this coating is a better catalyst than the amorphous iron silicates that initiate these reactions. Formation of a self-perpetuating catalytic coating on grain surfaces could explain the rich deposits of macromolecular carbon found in primitive meteorites and would imply that protostellar nebulae should be rich in organic material."

More recent studies of protostellar nebulae show that, far from being collapsing gas and dust clouds of roughly homogeneous structure, protostars are complex chemical systems with stable internal processes that circulate material in distinct patterns and that this circulation of materials across thermal gradients produces a distinctive, complex chemistry. In an article in Science Express (March 29, 2012) Complex Protostellar Chemistry, Nuth elaborates on the new, more complex model of protostellar interiors:

"Large-scale motion driven by conservation of angular momentum, together with more local convective cells above and below the hotter nebular midplane dynamically mix products of chemical reactions from many different environments throughout the nebula."

The result?

". . . [B]ecause the midplane is hotter than the outer boundary of the disk, convection will also mix materials vertically in the nebula. Ciesla and Sandford show that ice-coated dust grains, moving outward and subject to convection will be exposed to cosmic radiation that is sufficient to cause the same chemical effects seen in dark cloud cores—that is, the conversion of simple carbon-and nitrogen-containing molecules into more complex organic species—and so will have consequences for nebular chemistry."

The study by Ciesla and Sandford is summarized in this March 30, 2012, University of Chicago news release:

"Complex organic compounds, including many important to life on Earth, were readily produced under conditions that likely prevailed in the primordial solar system. Scientists at the University of Chicago and NASA Ames Research Center came to this conclusion after linking computer simulations to laboratory experiments. Fred Ciesla, assistant professor in geophysical sciences at UChicago, simulated the dynamics of the solar nebula, the cloud of gas and dust from which the sun and the planets formed. Although every dust particle within the nebula behaved differently, they all experienced the conditions needed for organics to form over a simulated million-year period. “Whenever you make a new planetary system, these kinds of things should go on,” said Scott Sandford, a space science researcher at NASA Ames. “This potential to make organics and then dump them on the surfaces of any planet you make is probably a universal process.” Although organic compounds are commonly found in meteorites and cometary samples, their origins presented a mystery. Now Ciesla and Sandford describe how the compounds possibly evolved in the March 29 edition of Science Express. How important a role these compounds may have played in giving rise to the origin of life remains poorly understood, however. Sandford has devoted many years of laboratory research to the chemical processes that occur when high-energy ultraviolet radiation bombards simple ices like those seen in space. “We’ve found that a surprisingly rich mixture of organics is made,” Sandford said. These include molecules of biological interest, such as amino acids, nucleobases and amphiphiles, which make up the building blocks of proteins, RNA and DNA, and cellular membranes, respectively. Irradiated ices should have produced these same sorts of molecules during the formation of the solar system, he said. But a question remained: Could icy grains traveling through the outer edges of the solar nebula, in temperatures as low as minus-405 degrees Fahrenheit (less than 30 Kelvin), become exposed to UV radiation from surrounding stars? Ciesla’s computer simulations reproduced the turbulent environment expected in the protoplanetary disk. This washing machine action mixed the particles throughout the nebula, and sometimes lofted them to high altitudes within the cloud, where they could become irradiated. “Taking what we think we know about the dynamics of the outer solar nebula, it’s really hard for these ice particles not to spend at least part of their time where they’re going to be exposed to UV radiation,” Ciesla said. The grains also moved in and out of warmer regions in the nebula. This completes the recipe for making organic compounds: ice, irradiation and warming. “It was surprising how all these things just naturally fell out of the model,” Ciesla said. “It really did seem like this was a natural consequence of particle dynamics in the initial stage of planet formation."

NASA's Stardust mission, which in 2004 captured and returned to Earth dust from the comet Wild 2, provided additional corroborating evidence of silicate transport processes. And isotope analysis provides additional evidence. The cometary dust included silicate crystals that could form only in the innermost regions of the solar system and that then must have been transported to more peripheral, cooler regions, where they were incorporated into comets. At later stages in a developing solar system, when planets are forming, the characteristic silicate material identifiable in the circumstellar dust includes a greater proportion of crystalline (as opposed to amorphous) silicates, and the organic content of the dust comprises increasingly complex molecules. This suggests a two-step process, in which simple organics are catalyzed near the protostar, then transported to cooler regions of the stellar nebula for further, more precise chemical processing. The second step relies on crystalline silicates. NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope has revealed similar processes operating in other galaxies. It might be a routine part of solar system formation that the relevant elements are brought together in the right kind of reactive environment to synthesize complex organic chemistry—a physiological process characteristic of baby solar systems. Ground-based studies also have revealed significant organic chemistry in protoplanetary disks around T Tauri and Herbig Ae stars.

Chondrites are a class of primitive meteor that includes the famous Murchison meteorite, which fell in (on?) the town of Murchison, Victoria, Australia in 1969. The Murchison is rich in organic material, including common amino acids. Chondrites generally are rich in organic material, but they are comprised primarily of chondrules, which are roughly millimeter-sized silicate-rich spherules, their constituents being dominated by the silicates olivine [(Mg,Fe)2SiO4], pyroxene [(Mg,Fe,Ca)SiO3], and silicon glass.

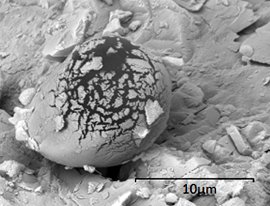

In June 2011, near the village of Tissint, Morocco, a Martian meteorite struck the Earth. Shattered pieces of the meteorite were recovered less than five months later. Its mineralogic content was determined to be primarily olivine-phyric shergottite. A team of U.K. researchers examining samples with electron microscopy discovered in the meteorite a number of spherical and spheroid bodies rich in carbon and oxygen, suggesting remnants of biological origin. One such structure is shown at left. The formation of these spheres, the researchers observe, "within the mineral matrix is not easy to explain by any non-biological processes. Biology, on the other hand, can provide an elegant explanation of these structures."

In aggregate, the foregoing findings support a model in which normal physicochemical processes in space are predisposed to produce complex organic chemistry and would have the time to do so. Just how complex remains to be seen, but it's not at all clear that a barely cooled planetary surface would produce anything similar. Such considerations lead directly to speculations about panspermia—the assertion that life on Earth arrived originally from outer space.

Moreover, because sedimentation and the turbulence of convection currents disrupt silicate crystallization on Earth, the semiconductor industry continues to work with NASA to investigate silicon crystallization in space. In weightlessness, silicon crystals can be grown larger and with greater purity—geometric regularity—than they can on Earth. This effect suggests that the silicon-mediated manufacturing of viruses and bacteria in space could occur very efficiently on a cosmic scale. Radiation conditions in space might even be responsible for biochemistry's homochirality.

With research continuing to push back the date of Earth's first living cells, it becomes increasingly difficult to defend a terrestrial origin of life, because there is not enough time for it to occur. If it ever would. And some bacteria and viruses now are known to be highly resistant to the harsh conditions of outer space, a peculiar attribute if life is of terrestrial origin. How can this resistance be explained in terms of evolutionary selection pressures?

Darwin's hypothetical "small warm pond" in which he imagined life to have arisen, might be an image less fitting than that of an extraterrestrial "big cold cloud."

![]()

The Star Larvae Hypothesis:

Stars constitute a genus of organism. The stellar life cycle includes a larval phase. Biological life constitutes the larval phase of the stellar life cycle.

Elaboration: The hypothesis presents a teleological model of nature, in which-

Stellar nebula manufacture bacteria and viruses in their interiors as they cool.

-

Biology evolves within an ontogenetic program that in its entirety, on- and off-planet, constitutes a generational life cycle of the stellar organism.

-

Technology plays a necessary role in evolution. It enables biological life to emigrate from planets to weightless space.

-

Postplanetary life manufactures the protons needed to create, then metamorphoses into, new stars.

-

A prescient complex of celestial religious motifs expresses humankind’s stellar calling. The star is the human imago.

-

Nature's metabolism encompasses the organic and the inorganic in a continuum of anabolic and catabolic exchanges.

| Tweets by @Starlarvae | |

| |

Home | Blog | About | Videos | Contact | Text Copyright ©2004-2017 Advanced Theological Systems. All Rights Reserved.

Privacy Statement: We use third-party advertising companies to serve ads when you visit our website. These companies may use information (not including your name, address, email address, or telephone number) about your visits to this and other websites in order to provide advertisements about goods and services of interest to you. If you would like more information about this practice and to know your choices about not having this information used by these companies, visit the Google ad and content network privacy policy.